Louise McGuane packed in her high-flying career as a global drinks executive to set up her own JJ Corry brand in County Clare. She talks to Barry J Whyte about reviving the art of whiskey bonding, her approach to risk and why she’s cautious about the American market

For the latter decades of the twentieth century, at the lowest ebb of Irish whiskey as it struggled to avoid dying out entirely, a curious set of relics pointed to its once vibrant past.

On the signs of countless pubs in towns around Ireland, sometimes painted over, were the words ‘whiskey bonder’.

This was a reference to an era in which distillers didn’t bottle every litre of whiskey they produced, but instead sold it to pubs and small businesses who would blend it and finish it themselves, creating an entirely new flavour and taste, and sell it under their label.

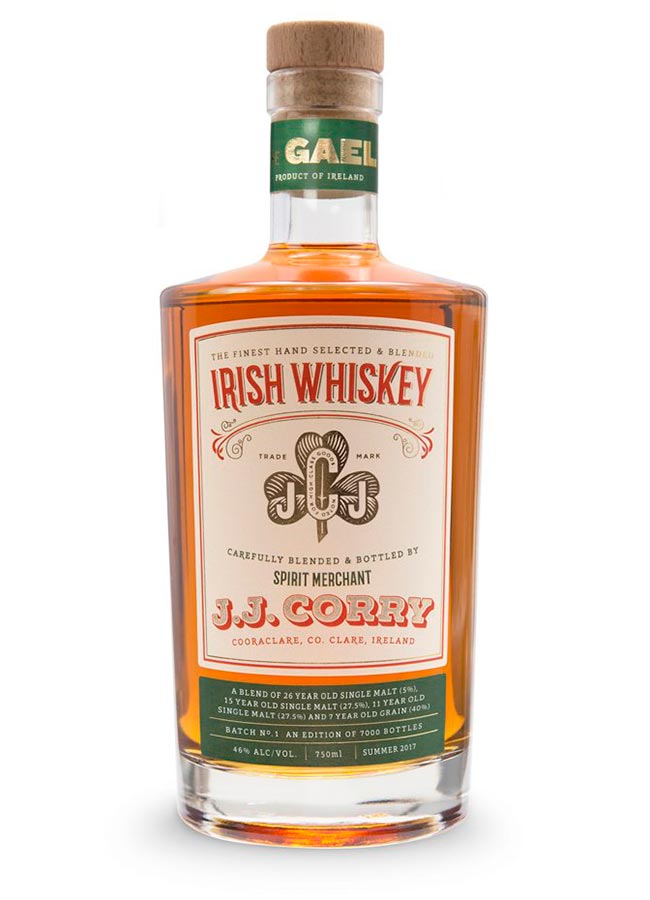

Now whiskey bonders, having been extinct for generations, are back and their revival can be credited to one person: Louise McGuane of JJ Corry Distillery in Co Clare.

Before deciding to set up JJ Corry, McGuane had spent decades in the drinks industry at a high corporate level, working first in Moët Hennessy on their wines, champagnes and cognacs, then in Pernod Ricard, before winding up in Diageo.

“That whole sequence had taken me from London to Paris to New York to Singapore — all over the world with a fairly helicopter view of the drinks industry,” she tells Business Plus.

“I could see brown craft spirits had become a thing. They were really starting to move in America, and that market always tends to set a trend globally.

“If it happens in America, you’re probably going to see a trickle down eventually,” she says.

It was a big risk, throwing away the security of a high salary and job protection to take a punt on the growth of Irish whiskey, but in a way she only recognises now, McGuane had a high tolerance for risk.

She also made some canny decisions early on, especially when it came to the question of building a very costly and time-consuming distillery, which was the only legitimate way to start a whiskey business in Ireland, or so the received wisdom held.

“Because, at the time — and now as well, to some degree — there were people who were just buying whiskey and throwing some fake 100-year-old brand out the door.

“It was extremely maligned, and people looked down on those kinds of brands,” she says.

“So when I discovered the whiskey bonding model, which I discovered purely through research, I thought ‘that’s interesting, there’s an authenticity there’.

“It’s a subcategory that was extremely important to the industry as a whole for hundreds of years,’” she says.

It’s a subcategory that wasn’t embraced by the multinationals who dominated the industry ten years ago, at the start of the boom, but they have since changed their minds.

“They’ve subsequently reclaimed it, and I’ll take credit for that, to be frank with you,” she says.

Bonding had another advantage, as well as being an authentic way to make Irish whiskey: it was less risky from a start-up perspective.

Building a whiskey distillery is an enormous capital risk, McGuane explains, and one that won’t pay off for at least three years, when the first spirit to come off the still has aged sufficiently to meet the regulatory standard to be called Irish whiskey.

“My business model was possibly a bit less risky than opening a distillery, because the capital that I was able to raise was put into buying whiskey that was already mature, and I was able to get to the market a bit faster,” she says.

But it’s what she does with that whiskey that really matters, McGuane says, and it’s not simply a question of decanting it into a bottle with a fancy label.

“Our job is to shepherd the stock that we purchase along the way and make it really unique and interesting through a series of interjections throughout the maturation process and the blending process,” she says.

“It’s expensive and it’s time-consuming, and it would be easier not to do that, but that’s what Irish whiskey bonding means.”

There are a lot of different levels at which she can make those interjections, from the selection of the initial spirit, to the purchase of casks in which to mature it, to the final decision of which whiskeys to blend and in what quantities.

As she explains: “We buy new-make whiskey, which is zero-year-old whiskey, and it looks like vodka. If I buy it from Distillery A, that is going to be different to what I buy from Distillery B.”

This is because of the quantity of grain or wheat or other ingredients they use. That has significant implications in terms of the flavour and taste profile of the whiskey, right off the bat.

“Let’s say if I have a whiskey — even if it’s a grain whiskey — and it has a bit more wheat in it compared to another spirit, then it’s going to have a more creamy mouthfeel, right?”

Then there’s the question of how to impart more flavour into that whiskey.

“So let’s say I have a number of sherry casks in front of me. The way I have selected my sherry casks is that I’ve gone to the wineries in Spain that make sherry and I’ve sat down with the winemaker and I’ve tasted the wines, right?”

There are several different varieties of sherry, all of which taste different and will have an effect on the taste during maturation, she says, whether it’s an Amontillado sherry with its hazelnut-like flavour, or PX sherry which has hints of chewed fruits, blackberries and dark chocolate, or Fino sherry, with more floral hints.

“So let’s say I throw the same liquid into three different casks, one of them’s gonna turn out nutty, another one’s gonna turn out floral, and the third one, then is gonna turn out kind of jammylike, and fruity,” she says.

Then she can mix and blend those any way she wants, with different choices significantly affecting the final taste of the whiskey.

“You’re kind of like a chef, trying to figure out what goes with what — that’s the game, that’s the art and the craft of it,” she says.

Like wine, it might change and develop over time, depending on those inputs and how they might change, but that’s the point.

For a premium whiskey like a JJ Corry, people are likely to buy it a couple of times a year, given its price tag.

In that sense, it’s more like an expensive bottle of wine, or a trip to a high-end restaurant.

“You don’t want to go to your Michelin-star restaurant and eat the same thing every single time for ten years,” she explains.

Like wine, she’s hoping that the quality of whiskey she produces cultivates brand loyalty — that the drink may differ from year to year, but it will always have a certain character and quality.

A certain JJ Corry-ness, as she describes it.

So far it’s an approach that’s served her well. The company has broken the million euro mark in annual sales and the brands sell worldwide.

While Irish whiskey is strongly pitched as an export product, JJ Corry does very well in its domestic market, and particularly in the counties around Clare during the summer tourism months.

It has also just expanded into Musgraves stores on a national level.

“We sell nothing from September to March — very, very, very little — but we have really leaned into owning our home territory,” she says.

Her brands sell around the world, including in 15 American states, but she warns anyone to approach the US in particular with some caution.

“I think there’s been a lot of dreams dashed on the shores of America for Irish whiskey brands,” she says, not least because it’s got a three-tier system with importer, distributor and retailer, all of whom take a cut as their whiskey passes through.

She advises others to “build the bejesus out of your brand in Ireland and the rest of the world” before approaching the US.

For the next few years, McGuane is focused on growth, with an aim of doubling that million euro a year in revenue in the short term.

At the end of 2022, JJ Corry had run up accumulated losses of €2.5m, after a loss for the year of just over €940,000, which is not unusual for a young whiskey company.

To date, McGuane has raised just under €4m, most of which went into buying stock, but with the benefit of hindsight she wonders if she should have raised more.

“It’s easier to raise €20m on day one than it is when you’re five years into the thing, quite frankly. So I wish that I would have been braver about what I was going to raise,” she says.

In the next few years, she expects to raise about €5m in a couple of different phases, which — with the bonding model now proven to work — will go towards buying stock and hiring people in sales roles.

She will likely need it, for the future of the spirits industry could prove a little choppier after ten years of heady growth, with the post-Covid slump, rise in cost of living, and increase in the price of supplies.

Will that affect Irish whiskey and, more to the point, will it affect JJ Corry? Probably to some extent, McGuane says, “You feel the pressure when your cork price goes up by two cent. It matters. Your margin goes down by two cent,” she says, by way of example.

She knows that there’s no wasted money at JJ Corry, “no sloshy spending”, so the company is likely to be well positioned and she’s confident about the next few years.

“But you have to crack on and deliver, you have to deliver revenues and you have to deliver profits, and you can be as maverick as you want but you have to be a serious business,” she says.

“There’s no point in sugarcoating it.”

Photo: Louise McGuane. Supplied